All the political talk about a "fiscal cliff," and a post by Peter Boettke, has led me to begin reading Democracy in Deficit by Buchanan and Wagner. I think the opening paragraph in the first chapter of Democracy in Deficit suggests a very simple way of thinking about the fiscal issues front and center in the news today:

In the year (1776) of the American Declaration of Independence, Adam Smith observed that "What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom." Until the advent of the "Keynesian revolution" in the middle years of this century, the fiscal conduct of the American Republic was informed by this Smithian principle of fiscal responsibility: Government should not spend without imposing taxes; and government should not place future generations in bondage by deficit financing of public outlays designed to provide temporary and short-lived benefits.In other words, government should generally operate without running a deficit. Government should generally pay for its activities each year with annual tax revenues.

If you agree this is a reasonable idea, then perhaps you will wonder about the so-called fiscal cliff that the President and members of Congress are bickering over these days. The idea of the fiscal cliff is that Congress and the President have "bound" themselves by past actions in ways that will, on January 1, result in (1) an increase in income tax rates (for every taxpayer), and in (2) automatic across the board cuts in government spending. If you haven't been paying attention to politics lately you might wonder why the President and Congress would take action in the past that would bind them to (1) and (2) today. The answer seems to have something to do with the fact that the President and Congress have been borrowing quite a lot of money to finance their activities of late. I will show you how much borrowing in two charts below. It seems that the President and members of Congress recognized in the past that they really aren't very good with budgets and fiscal responsibilities, and thus they concluded that if they wanted to start borrowing less money they would have to bind themselves to (1) and (2). There must be some truth to the idea that they aren't very good with budgets because we are now less than a month away from (1) and (2) happening, and what are the President and members of Congress bickering about? Yep, unbinding themselves from (1) and (2) so that they can borrow more money.

How is it that we are now facing a "fiscal cliff?" Maybe our political leaders see this as a cliff because they can't face up to the idea that they should be more responsible than they are with the budget of the United States. Or it may be that our political leaders and others see a cliff because they believe that more tax revenue and less spending will mean a new period of recession for the country. Or, it may be that our fearless leaders are hoping to deflect our attention from the mountain of loans they have been taking out lately by telling us to pay attention instead to the cliff that is (1) and (2).

Given all the public bickering and finger pointing, I'm thinking the last alternative makes a lot of sense. After all, if the President and Congress have been borrowing too much money in the past few years, then it seems that the quote from Democracy in Deficit would suggest they need to get out a pair of deficit scissors and cut the size of their borrowing. What would deficit scissors be? Well, pretty much something like (1) and (2). One blade of the deficit scissors would be more tax revenue while the second blade would be cutting what they spend each year.

Should the President and Congress get the deficit scissors out? You'll have to decide for yourself, of course. But, after showing you some numbers that I found in the FY 2013 Budget Proposal of President Obama, I'll tell you my answer. These numbers come only as close to the present fiscal year as FY 2011 because that is the last year for which actual information is available. I do not present estimates. The first chart shows the historical record of U.S. Government receipts and outlays as percentages of GDP. Outlays are shown in red, and thus for any year that the red trend line is above the blue trend line the U.S. Government ran a deficit, i.e., Congress and the President borrowed money. It looks like the President and Congress began to borrow more each year, compared to the past experience, from around 1970 on. There is an exception which is shown by the

four years of surplus around the end of the Clinton presidency. In most of the years after those four years of budget surplus the President and Congress borrowed pretty heavily. The last three years in the chart show very heavy borrowing.

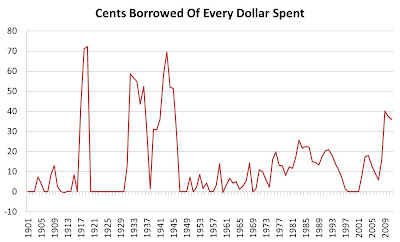

I don't think it is really easy to understand the meaning of a government deficit when expressed as a percentage of GDP. The next chart shows the deficit in terms of the cents borrowed out of every dollar spent by government in each year. For any year in which government's budget was in surplus

the cents borrowed is shown as zero. The information in this chart begins in 1900 and ends with the 2011 FY. Notice that outside the years that involve either a world war or the Great Depression, the US Government seldom borrowed more than 20 cents of every dollar it spent. It also appears that over the period of years since WWII the US Government's reliance on borrowing increased early in the decade of the 1970s. The US Government's willingness to borrow seems also to have increased recently. In the 2009 FY it borrowed 40 cents of every dollar it spent, in 2010 FY it borrowed 37 cents of every dollar spent, and in 2011 it borrowed 36 cents of every dollar spent.

I suggest that the President and Congress have borrowed far too much money in recent years. Borrowing thirty to forty cents of every dollar spent is far too much. I also suggest that if you look again at the first chart, it is reasonable to conclude that the last three years in the chart display a significant increase in the spending habits of the President and Congress. Yes, there was also a decrease in tax revenues during the last three budget years, which is of course what happens with recession. Given the proclivity of the red spending trend line to be above blue revenue line since around 1970, it seems to me the borrowing problem of the President and Congress results from their proclivity to spend too much.

In any case, except for relatively unusual circumstances (e.g. a world war), it seems to me that the President and Congress should be budgeting for a surplus, or for a very small deficit (perhaps five or ten cents for every dollar spent). The fiscal cliff looks to me like deficit scissors that are really needed at this point to begin to get the President and Congress to be fiscally responsible with our money and the money of future generations. My preference is for the President and Congress to spend less rather than raise tax rates on any of us, but I suggest ending the unjustified borrowing is the greater priority at this time.

What do you think? Should we fear the fiscal cliff, or should we get out the deficit scissors?